Chap. IV. -- ALL SOULS' CHURCH.

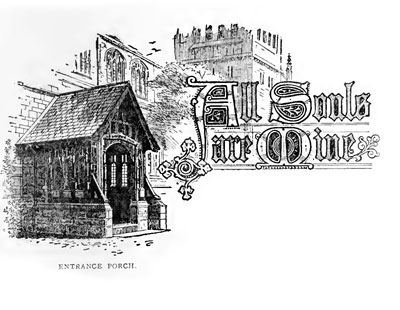

ENTRANCE PORCH.

"All Souls are Mine" is the inscription over the porch from which the Church of the Second Congregation derives its name. At a Congregational Meeting, held on 18th June, 1896, the choice of a name for the new Church was considered, when it was unanimously decided to adopt the name "All Souls." The reason for the choice was expressed by Mr. Fripp on that occasion as follows:-- "All Souls appeared to them an ideal name for a Non-Subscribing Church. It was comprehensive, it excluded no one, and it expressed the fundamental principle of religion that all souls were God's. Men and women and children, of all nations, sects, and parties, belonged to God, and were kindred with Him. They were all souls, spirits, with a kinship to the Highest, with a longing and yearning for Him; the offspring not merely of the ground, not merely of something beneath them, but of something above them. That truth, the growing emphasis on which would in course of time transform the world, was the living essence of Christianity uttered by Jesus in the opening words of His prayer, 'Our Father,' and in the declaration of St. Paul that the Spirit of God cried within the heart of man, saying, 'Abba, Father.' Ezekiel had said, in the eighteenth chapter of his collected writings, the fourth verse, in God's name, 'All Souls are Mine.' "

"All Souls are Mine" is the inscription over the porch from which the Church of the Second Congregation derives its name. At a Congregational Meeting, held on 18th June, 1896, the choice of a name for the new Church was considered, when it was unanimously decided to adopt the name "All Souls." The reason for the choice was expressed by Mr. Fripp on that occasion as follows:-- "All Souls appeared to them an ideal name for a Non-Subscribing Church. It was comprehensive, it excluded no one, and it expressed the fundamental principle of religion that all souls were God's. Men and women and children, of all nations, sects, and parties, belonged to God, and were kindred with Him. They were all souls, spirits, with a kinship to the Highest, with a longing and yearning for Him; the offspring not merely of the ground, not merely of something beneath them, but of something above them. That truth, the growing emphasis on which would in course of time transform the world, was the living essence of Christianity uttered by Jesus in the opening words of His prayer, 'Our Father,' and in the declaration of St. Paul that the Spirit of God cried within the heart of man, saying, 'Abba, Father.' Ezekiel had said, in the eighteenth chapter of his collected writings, the fourth verse, in God's name, 'All Souls are Mine.' "

But although the name of All Souls was chosen for the Church, the existence of the Second Congregation has in no way been interfered with. The corporate body is quite distinct from the name of a building, and the lease of the ground on which All Souls' Church is built is held in the names of the Trustees of the Second Congregation of Protestant Dissenters in the Town of Belfast.

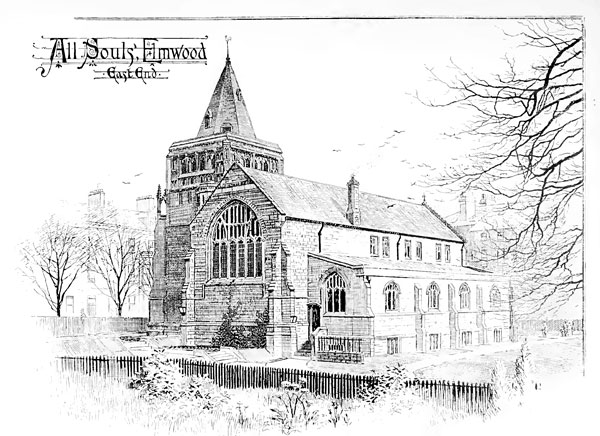

As soon as the Congregation felt it desirable that they should leave Rosemary Street, with all its dear and honoured associations, they showed a determination to spare no pains to have a Church that would remain for years to come to be a thing of beauty. The undertaking was a heavy responsibility, but the awakened energies of every member proved it to be a work of love. Eighteen months after it was decided to build, the foundation-stones of the six pillars were laid, and twelve months later All Souls' Church was opened as a place of worship. It may be described as a rough rubble building, with ashlar dressings and green slate roof, late fourteenth century in style, consisting of nave and chancel under one roof, with aisles and clerestory, a low broad tower and spire, and a wooden porch.

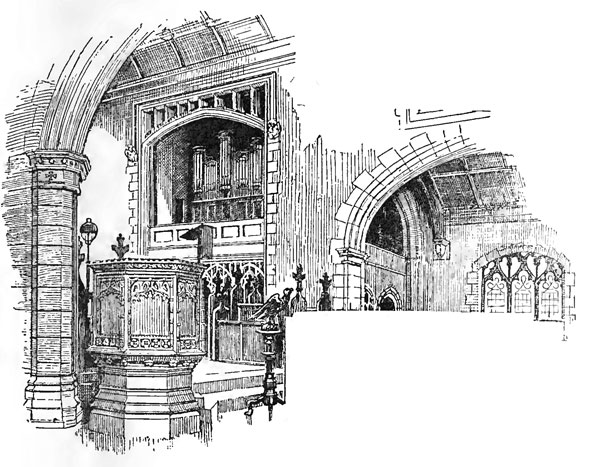

But, apart from the mere architectural beauties, the building possesses some features which are deserving of the closest attention. The chancel and nave are unseparated by iron gates, which in many of the old cathedrals of Europe stand as a relic of spiritual corruption. Although iron gates are not common in parish churches, we often find an archway separating the Chancel from the Nave of the Church, and in almost all cases do we find a Communion Rail. None of these distinctive lines of separation are to be seen in All Souls'. Those barriers, which created an exclusive caste, superior to and independent of all temporal power, were broken down by the Reformation, of which Wycliffe was the morning star and Luther the noonday luminary. Personal responsibility and private judgment were established, and the laity wrested from the clergy the right to remonstrate and, if needs be, to rebuke them.

In this respect the building will stand as a monument not only of the Reformation, but of the spirit of freedom that occasioned the formation of the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster. Tyranny in all its forms, whether it be that of an individual seated in the Papal chair, or an Assembly of Divines, bound by the fetters of the Westminster Confession of Faith, is inconsistent with the freedom of human thought which the Reformation strove to accomplish. When the Synod of Ulster felt it incumbent upon them to impose fresh restrictions upon liberty of conscience and freedom of inquiry in matters of faith, many ministers and elders objected to such a proceeding as an invasion of their rights. The result of the protest was the formation of the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster, and at their first meeting, which was held in Belfast in 1830, they held out the right hand of fellowship to the Presbytery of Antrim, which had been excluded from the General Synod in 1726. There was no desire on the part of the Remonstrant Synod to promote the advancement of any set of doctrinal opinions to the exclusion of others, as each Congregation had the unrestricted right to elect a minister entertaining such views as they themselves might approve.

That was the principle which actuated the members of the Second Congregation when they decided not to brand the new Church with the name Unitarian. The Congregation had changed with the times, and Trinitarianism had given way to Unitarianism; but never in its history had the building been stamped with a particular Theological brand. The liberty which a previous generation had enjoyed, and which enabled them to advance with the enlightenment of the world of Science, was respected, and the members felt that future generations were entitled to the same freedom.

Another feature of All Souls' Church, and one which attracted considerable attention when the building was completed, is the short spire which surmounts the tower. Many people in Belfast, who had been accustomed to the lofty spire, such as that graceful structure of our Trinitarian friends in Elmwood, regarded the short spire as a departure from the orthodox style of architecture. But instead of being a departure, it is in strict accordance with the style of the church, which is early English. The tower was a distinguishing feature of the Norman architecture, which was introduced into England at the Conquest. It was generally square, of rather low proportion, and seldom rose much more than its own breadth above the roof of the church. The early English gave greater variety of design and proportion than their predecessors, and in many cases the towers were very considerably ornamented, the upper stories being usually the richest. Some of these found their way into Ireland, and the old church of Leighlin,[1] in County Carlow, which was built during the last decade of the fourteenth century, had a tower and spire which bore a very close resemblance, in outline, to that in All Souls.

The ceremony of laying the foundation stones[2] was performed on 25th October, 1895, when

Mrs. Malcomson laid the stone at the base of the eastern column of the south aisle.

Miss Benn laid the stone at the base of the western column of the south aisle.

Mrs. W. J. Pirrie laid the stone at the base of the western column of the north aisle.

Mrs. James Campbell laid the stone at the base of the eastern column of the north aisle.

Henry J. M'Cance, Esq., J.P., D.L., laid a stone in the north-east respond.

Samuel C. Davidson, Esq., laid a stone in the north-west respond.

The opening services were held on the 11th October, 1896, when the Rev. Joseph Wood, of Birmingham, Tate Lecturer at Oxford, preached at both morning and evening services to a crowded congregation. In the morning he took as his text, "All souls are Mine," Ezek. xviii. 4, and the concluding words of the sermon were as follows:--

"You have dedicated this beautiful church to what is universal in religion and in the human heart, by dedicating it to 'All Souls.' These walls are to bear witness to no sect, no party, no narrow exclusive creed; they are to speak for ages to come of your faith in humanity, the faith that endows all that is human with work and sanctity. In the Church of All Souls there is no high and no low, no superior and no inferior, no destruction of classes and masses, but all one in that fair brotherhood of man that Christ came to establish. You have dedicated this church to the faith that overleaps the barriers of wealth and race, of narrow convention, social prejudice, and personal dislike. This church is for no clique of the select, but a house for all men -- a house not merely for elder brothers that they may be feasted and robed, but a house that gives itself the privilege of welcoming the prodigals of humanity with dancing and with song. This church is to lay its hands on mixed humanity, and draw them all in, pouring upon them the splendours of light and love. God keep this church faithful to its great name, to its high calling, and to its universal mission. Under its benediction may duty become more sacred and men more precious. Here may the poor and the needy, the tempted and the tried, the old and the young, find a home of peace. Peace be within these walls; peace to all souls that enter here; peace to minister and peace to people. Hear their prayer, O Lord, realise their hopes, and establish the work of their hands."

The opening services were continued on the two following Sundays by the Rev. Frank Freeston, of Kensington, and the Rev. Henry Gow, of Leicester, when the offertories amounted to over £400.

Several of the members have already contributed to the decoration of the church by the following presents:-- A beautiful brass eagle lectern, a communion cloth, worked in silk by a lady member, and two Glastonbury chairs in oak for the chancel, with cushions. The late Mrs. Malcomson made provision, by her will, to have the south-western window erected in stained glass in memory of her daughter, Mrs. Nelson, which window will be alongside the memorial tablet to her son, Lieutenant Malcomson.

Shortly after the church was opened, a dark shadow fell on the Congregation by the death of Mr. John Ritchie, who for forty-two years had been the secretary. He was deeply interested in everything connected with the welfare of the Second Congregation, and worked assiduously in the building of All Souls'. On the 21st July, 1897, the coffin was placed in the Chancel, and the minister conducted a funeral service, in which he referred to the fine qualities of his manly nature. His remains were conveyed from the church, amid the mournful strains of the "Dead March in Saul," to the Borough Cemetery, where, in the presence of many friends, they were deposited in the family grave.

A letter of sympathy was subsequently sent to Mrs. Ritchie, on behalf of the Congregation, expressing the great loss which they had sustained. "We cannot adequately express our indebtedness for his long services for more than forty-two years. He was not only a comrade in the cause, but an invaluable leader, whose experience and devotion and enthusiasm, as well as his painstaking interest and staunch support, have helped us in days of difficulty, and enabled us to continue our work with renewed vigour."

The Congregation are still anxious to preserve freedom of conscience, in accordance with the traditions of the past, and refuse to impose any subscription to a particular theological form of belief, as may be seen from the following, which appears in All Souls' Church Kalendar:--

"No doctrinal test is imposed as a condition of membership in this Church. We recognise that all souls are born of God and partake of His Spirit, and this divine Sonship, not the acceptance of particular theological opinions, is the bond of our Religious Fellowship. Seeking Truth and the Mind of Christ, we unite for the Worship of God and the Service of Man."

Notes:

- See the engraving in Ledwich's Irish Antiquities, p.522.

- Each of the foundation stones is denoted by a cross, such as that shown on the north-east respond, p.97.